I happen to be colorblind; red-green specifically. Here are some good facts about colorblindness so I won't have to go into it. (I do get asked "what color is this?" way too often when I admit my handicap)

A couple of the facts:

#01 99% of all colorblind people are not really color blind but color deficient; the term color blindness is misleading.

#06 Strongly colorblind people might only be able to tell about 20 hues apart from each other, with normal color vision this number raises to more than 100 different hues.

#20 Colorblind people feel handicapped in everyday life, and almost nobody recognizes this.

#29 Some people get rejected from a job assignment because of their color vision deficiency.

#32 Red-green color blindness doesn’t mean that you are only mixing up red and green colors, but the whole color spectrum can cause you problems.

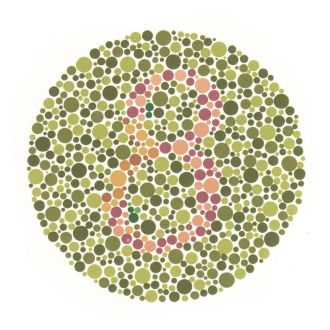

#41 The most often used types of color blindness tests are: pseudoisochromatic plates, arrangement test, and the anomaloscope.

Here's a Ishihara Color Blindness Test Plate that's just one of a few ways to test for colorblindness. I can just barely make out the number that's in there. As if someone turned the contrast way down.

In kindergarten, I used to color people green or brown because that was the closest color crayon I had and I didn't really see the problem. In first grade, I had labels put on my colored pencils for the red, green, and brown. Those dumb maps in geography, social studies, and history textbooks always pissed me off because, while I could tell the different regions were different shades, I couldn't match them up with the key. It causes issues.

But being the precocious introverted child I was, contemplating the way I viewed the world inspired deep thoughts. Were the different names we assigned colors arbitrary? Yes, we all agree that a given object is called by the same color, but how are we to know that the color of an object I see is perceived as the same color by another person? I understood the physics of why different objects appear different colors, but if my consciousness was placed in another body, would colors be the same?

What did this imply about my other senses? Does everyone really perceive salty the same way? What about hot and cold? What about animals with other sense organs like a snake's ability to sense the infrared or a sharks ability to sense electrical impulses, what are we missing out on? What did this imply about the true nature of reality? And I was just in grade school!

Skipping to Buddhist terms, this is what is meant by the "five skandhas are empty." Skandha is translated as heap or aggregate in English. They are the things that make up an object we perceive.

They are:

- Form - the internal or external matter that is defined by the senses. This is different than the Western idea where form exists independent of ourselves with properties for our senses to observe. An object has different forms attached to it for each of our senses.

- Sensation - the raw sensing of an object independent of thought. Sensations fall under the categories of pleasurable, painful, or neutral.

- Cognition - the organization of form through sensation by thought. The mind gets involved and starts to sort the raw sensation.

- Mental formations/Volition - cognition triggers impulses and opinions arrive based on previous experience. Re-cognition

- Discernment/Consciousness - this is awareness without conceptualization. Becoming conscious of something for what it is and is not. Most popularly the dichotomy between "self" and "other" or "good" and "evil."

So my little philosophical crisis really opened the door and waited for this concept years later. Where exactly does color exist? Is it form? Maybe. Pretty much everything, every physical object at least, definitely has some sort of property that we observe visually.

What about sensation? For the most part color is neutral, before cognition at least. We either sense something has color or it doesn't. This would be where my colorblindness changes the game for me, since there is a difference in the way my sensors (eyeballs) receive data.

Cognition is the first step where the mind is involved, our brains as computers organizing the raw data from our eyeballs. Different people have different brains, so color could be interpreted differently in the brain. The physics and the chemistry are all the same here, but there's no way to tell how the brain organizes the info once it's in there.

At the mental formation stage, we now label a perceived and recognized color as what we've agreed it should be called so any damage that could be done by the emptiness of color is done.

Discernment is a problem for the colorblind since our perception of color leaves us with difficulty discerning (see it's right there!) what color we see. In my case the red-through-brown-to-green is an issue as well as the red/purple/blue. While I can tell red is not blue and green is not red, yellow is not purple, those two spectrum blend like white/gray/black. Just as normal people may have trouble telling where gray becomes black, I have trouble telling where purple becomes blue. When side by side, it's easy, but hold up a dark purple shirt towards the blue end of the spectrum, I may not see enough red in it to discern that it's purple.

I always had trouble with what emptiness in a Buddhist context really meant, bringing my own ideas of what the word emptiness means. After looking at it in the context of the five skandhas with this example, I think I have a better grasp on it.

So form is empty because we can't perfectly/directly perceive true reality. But emptiness is form because there is something to perceive. But nor is either of them true because they are creations of the mind, which is the sixth sense.*

It was comforting to find this as a teaching and to know that while I thought so at the time, I hadn't lost my grip on reality before entering high school.

--------------------

*In Buddhism, the mind is considered a sense because the world of our thoughts is just as real as what's "outside" our selves because there is no line separating the two worlds. You either get it or you don't, I don't want to go into explaining it here.

No comments:

Post a Comment